Screenshot of the trailer for King of Jazz by There Stands the Glass.

Top Ten Albums (released in April, excluding April 30 titles)

1. Damon Locks and Black Monument Ensemble- Now

Another urgent missive from Chicago.

2. Dopolarians- The Bond

3. Brockhampton- Roadrunner: New Light, New Machine

The worst album by the world’s best boy band.

4. Max Richter- Voices 2

5. John Pizzarelli- Better Days Ahead: Solo Guitar Takes on Pat Metheny

6. Bryce Dessner and the Australian String Quartet- Impermanence/Disintegration

Street hassle.

7. Toumani Diabaté and the London Symphony Orchestra- Kôrôlén

Stunning 2008 concert.

8. Arooj Aftab- Vulture Prince

Secular adhan.

9. Florian Arbenz, Hermon Mehari and Nelson Veras- Conversation #1: Condensed

10. Field Music- Flat White Moon

Top Ten Songs (released in April, excluding April 30 titles)

1. Cupcakke- "Mosh Pit"

Watch your step.

2. Georgia Anne Muldrow- "Unforgettable"

That’s what she is.

3. Trineice Robinson and Cyrus Chestnut- "Come Sunday"

Blessed balm.

4. Cello Octet Amsterdam- "8"

Circular strings.

5. Bree Runway- “Hot Hot”

Sizzling.

6. Tierra Whack- "Link"

Connected.

7. Rubén Blades and the Roberto Delgado Orchestra- "Paula C."

Swing-infused salsa.

8. Sons of Kemet with Kojey Radical- “Hustle”

Show you something.

9. Sonder featuring Jorja Smith- “Nobody But You”

Quiet storm.

10. Bill MacKay and Nathan Bowles- "Truth"

Gimme some.

Top Ten Movies (viewed for the first time in April, in lieu of live music)

1. Journal d'un curé de campagne/Diary of a Country Priest (1951)

Tristesse existentielle.

2. Captain Salvation (1927)

Gospel ship.

3. Agnes of God (1985)

Montréal miracle denied.

4. Bianco, rosso e…/Red, White and... (1972)

Sophia Loren plays an emancipated nun.

5. Imitation of Life (1959)

Annie isn’t okay.

6. The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

Que sera, sera.

7. Foreign Correspondent (1940)

Let’s go to war!

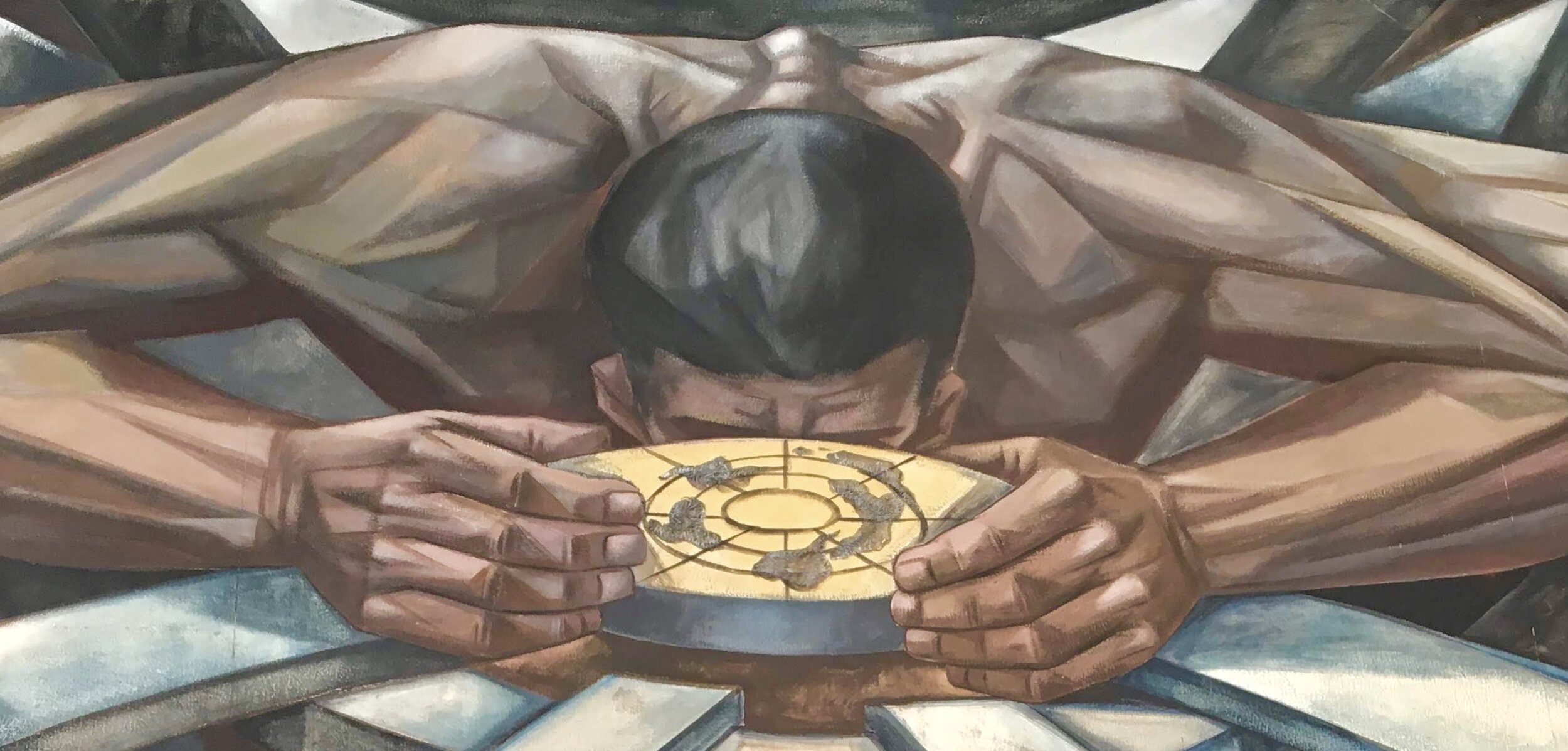

8. King of Jazz (1930)

9. Castle in the Air (1952)

Cheerio.

10. Honeysuckle Rose (1980)

Righteous music. Wretched movie.

March’s recap and links to previous monthly surveys are here.